OpenAI's goal is to build artificial general intelligence (AGI), which they define as "a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work". The other AI labs—including Anthropic, Meta, DeepSeek, and Google—have made similar claims. The CEOs of these companies think they might achieve it in just a few years, some saying as early as 2026.

While the exact timelines are still in doubt, there is a very real chance AGI arrives in the next few years.

Consider the trendlines. In 2019, state-of-the-art AI models couldn't write a coherent paragraph; by 2023 they were doing as well as the average candidate in human bar exams.1 In 2023, the top AI models were resolving 4.4% of a set of real-world example coding problems; by the beginning of 2025 they were resolving 49%. Other AI systems recently scored above the 99.5% percentile of expert humans on competitive programming problems. On multiple-choice science questions selected to be hard for everyone but PhDs in that specific field to answer, AIs improved from barely better than random guessing in mid-2023 to better than the human experts by the end of 2024. General computer-use capabilities are lagging behind pure-text skills, but have gone from near-zero capability to closing half the gap with humans within the last year.2 Researchers have even demonstrated a new Moore's law: the length of tasks AI can complete is doubling every seven months.

Governments are noticing this. The top recommendation from the Congressional US-China Commission in 2024 was for Congress to "establish and fund a Manhattan Project-like program dedicated to racing to and acquiring an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) capability". On the first full day of his second term, President Trump joined the CEOs of OpenAI, Softbank, and Oracle to announce Project Stargate, which intends to invest a total of $500 billion to build AI infrastructure.

If the industry and government consensus is even close to correct—and AGI is about to show up at your workplace—what is going to happen to your job?

This technology is different

Imagine you are the CEO of a large company.

In the 2000s, laptops became widely available. Instead of clunky desktop computers, your employees could now work from anywhere. They could take detailed notes in meetings and collaborate in the breakout room.

So you bought all your employees laptops. It made nearly all of them more productive, which resulted in increased profits for your company. But the laptops couldn't replace the analysts, because you couldn't give a laptop a task in plain English and expect them to do it. Instead, you needed the analysts to use laptops to access their benefits.

Fast forward to 2030. A big AI lab just released a new AI system. It completes any task 20% faster and 10% better than any of your junior employees. Running it to do the work of one employee costs $10,000 per year – that's at least an 80% cost reduction. It might let your best analyst do the job of 10, or automate the analyst class entirely.

Maybe you like your existing employees and are skeptical of this new system. You integrate it as a trial, and in a year it's outperforming all of them. In fact, keeping humans in the loop slows down the system and produces worse results.

Why wouldn't you fire your junior employees? They are more expensive, worse at the job, and unreliable. Sure, Mike interviews well and is nice to be around, but companies fire people their leadership personally likes all the time. And if your company doesn't fire them, you will be crushed by competition that does.

We believe this pattern extends throughout the economy. Junior employees at large firms will lose first, through a combination of hiring slowdowns and some firings. As AIs get better and better, AI will climb the corporate pyramid and replace workers one by one. Eventually, in many industries, there will be competitive pressures that force companies to stop hiring and start firing throughout the organization. This will begin in white collar firms, but will eventually impact every sector.

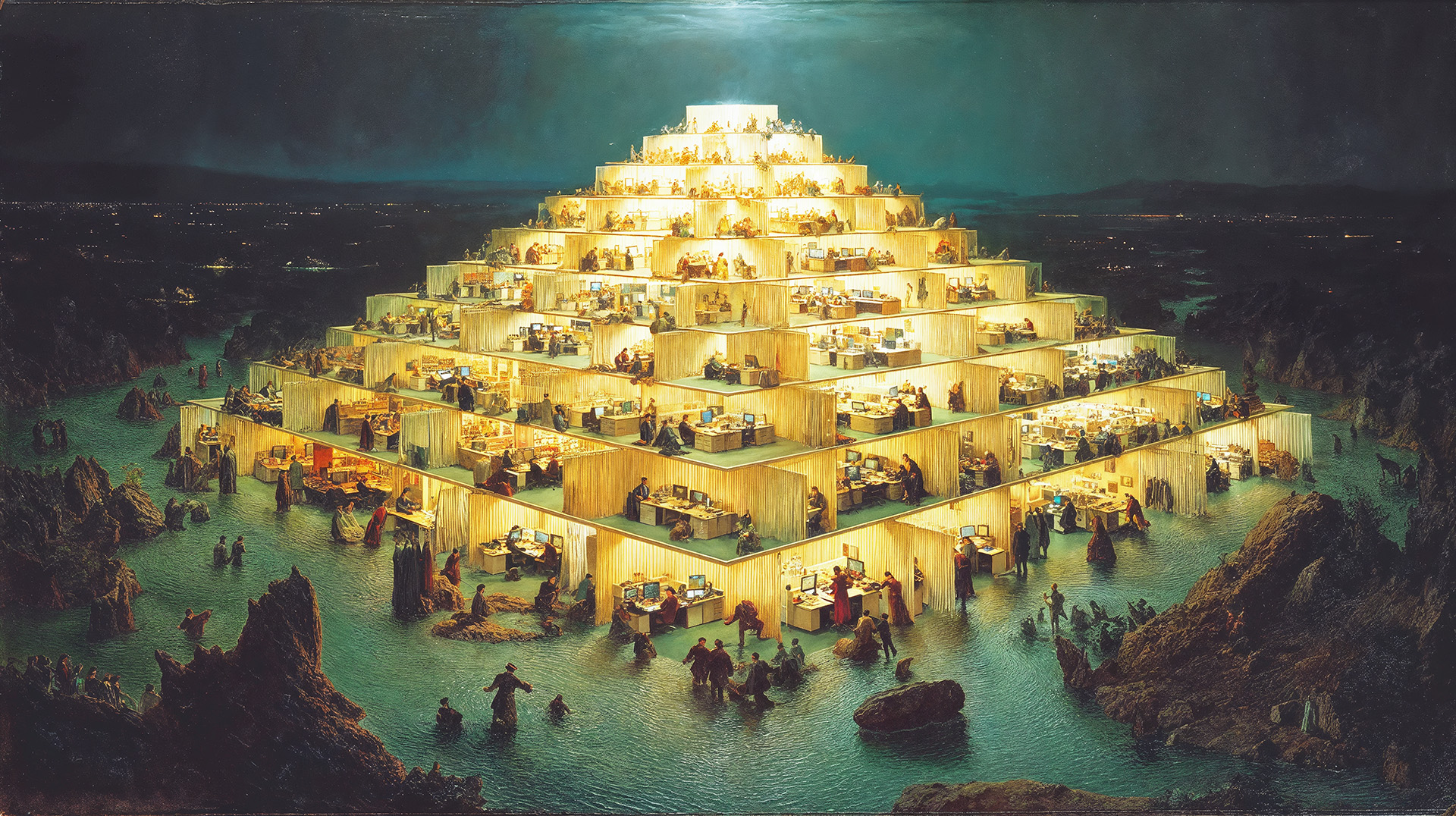

We call this pyramid replacement. How does it work?

AI in the corporate pyramid

White collar work in medium-to-large firms is uniquely exposed to AI automation, especially relative to other jobs. Robotics looks farther away than AGI, and the companies with physically-automatable work hire and fire differently than large white collar firms. Small businesses hire with less clear structures, with fewer easily-automatable employees and less clearly defined work.

For this analysis, we will focus on white collar companies. Their corporate org charts look like pyramids, with many junior employees at the bottom and fewer senior employees at the top:

Entry-level employees don't stay entry-level forever. Many of them become ready for a promotion, which means they can do more valuable work for the company. Some of them find another job and leave. At the same time, many of the middle to senior employees leave, retire, or otherwise stop working for the company.

All of this creates room for talent to flow upwards, but it requires the firm to regularly replenish the organization's bottom layers.

So every year, companies hire fresh talent from the best universities they can recruit from. They hold career fairs, take on interns, and spend lots of time training these smart but low-context individuals. Then, they give them the firm's simplest tasks. It's thankless, but it teaches them how the company works so they can move up the pyramid and manage future entry level employees.

When the first wave of AI agents arrive that can produce entry-level work outputs at a much lower cost than a human employee, companies might decide to:

- Do nothing, out of inertia

- Fire everyone, to maximize benefits

- Adopt it slowly, by just not hiring more people

Some firms might do nothing. We expect they'll regret it quickly—one of their competitors will adopt it, and their productivity gains will help them earn significant leads. Competitive pressures will be a strong force towards adoption. Most firms won't fire everyone the day such a tool is released, and the few that do will suffer. This system might be slightly better and a lot cheaper, but there will still be some glitches to iron out.

That leaves everyone else: the slow adopters. We suspect most firms will spend some time rolling out this tool. Once they see that it increases their best junior employees' work, they'll start to wonder why they hire so many entry-level analysts.

We think the first wave of AI employees, likely a combination of specialized LLM scaffolds from startups and natively agentic models from the labs, will allow companies to shrink their hiring costs without firing anyone. Instead, they'll slash hiring.

This pattern would repeat as new AI systems are released. These systems may be natively more directable, and will work without intervention for longer.

At this point, a firm will need very few entry-level employees to complete basic tasks. As existing employees get promotions, hiring will get slashed once again.

New AI systems are released. This time, the new AI agents do the work better when the entry-level employees don't interrupt them. Most managers manage more AIs than humans, and increasingly complex work is becoming automatable.

Companies have an expensive problem on their hands. They don't want to fire large swaths of employees for reasons of optics and inertia, but they could greatly benefit from laying off the large numbers of redundant employees.

For some firms, it'll take a shock—a recession, a downturn, or a bad quarterly earnings report—to announce layoffs as a cost-cutting measure. In the most competitive sectors, this action might happen faster. Either way, the most junior layers of the pyramid will disappear entirely.

Once again, the systems get better. This time, they unlock the ability to do all of the medium-horizon tasks in a company.

The market is expecting the next termination wave. While public resentment is growing, the shareholders will demand the productivity benefits to increase earnings. Plus, all the other firms are doing it. If the firm doesn't automate most of their work, they'll lose to their competitors. The pattern repeats, but this time it's even harsher.

Once again, new systems get released. They can now do all intellectual labor in the company, and they do it better without senior management in the loop. Many firms make the call: they only need the C-suite.3

Some time passes, and the AIs get even better. Now, they can track every interaction the company has, both internally and externally. A swarm of them can execute every decision, and the best of them can make strategic decisions exceptionally fast.

The board of some firms might realize that the C-Suite is now less capable of managing the company than the best AIs. CEOs are forgetful, and they don't have total insight into everything their company is doing – but their AI systems do.

This time, the board makes the call. For a small number of firms, the best performing version of their org chart is one without any human employees at all4:

Some caveats are needed

Diffusion barriers—things like regulatory barriers, investor or leadership skepticism, a lack of automation pressures from competing companies, high costs or use limitations, labor or union pressures, or a lack of economic downturns—could all slow this process down.

You may see a more jagged effect than this model demonstrates. Some jobs (ex: software engineers) are more immediately automatable than others, even at the same level of seniority. You could model this as a pyramid for each corporate function. Those have pyramids within a large organization, and will likely follow a similar pattern. Currently it seems like tasks that require planning and execution over longer time-horizons will take longer for AIs to automate, and it will be harder for AI companies to train AI models to do well on criteria that are harder to objectively judge.

Some white collar industries will be much more resistant to this than others. Tech companies could be largely automable with one or two more leaps in AI performance. Other white collar industries might rely on prestige, signalling, or soft skills that will be harder to automate. This probably doesn't matter at the entry level, but it matters for senior employees who do lots of important, interpersonal work.

Finally, this is a default trajectory for large companies. Tech or governance interventions could dramatically change this pattern.

The future of work?

To put it bluntly, traditional white collar work, the economic engine of developed economies, is unlikely to survive the AI revolution. This isn't a 2050 or 2100 problem – it is a problem for today's entrepreneurs, policymakers, and institutions.

The popular thing is to claim that new, better jobs will be created, and that wages will rise as a result. But when economists actually take AI seriously, they seem to reach different conclusions. Modeling by Korinek and Suh demonstrates that by default, wages plummet:

Matthew Barnett outlines several possible mechanisms of wage decline.

First, if AI results in a massive increase in labor supply, capital could become more of a constraint than labor. The returns to additional labor—machine or human—go down while those to capital go up. This means lower wages and higher returns to capital.

Second, when production requires fixed inputs like land, these fixed inputs can capture ever-larger shares of output as other inputs scale. This was essentially the pre-industrial Malthusian state of the economy: bottlenecked by land, and with subsistence wages for labor.

Third, humans have a higher "biologically imposed minimum wage" than AIs. We need to eat, and the efficiency of our brains is fixed. AIs don't have such limitations, and therefore their presence in the labor market might drive wages below the human subsistence level.

Barnett concludes:

All things considered, I am inclined to guess that there is roughly a 1 in 3 chance that human wages will crash below subsistence level before 2045. While this figure may appear alarmingly high to some, I personally consider it somewhat low, as it partially reflects my tentative optimism that technological progress will complement human labor even after AGI, keeping wages from crashing all the way below subsistence level in the near term. In the longer term, I'd guess the probability that human wages will fall below subsistence level before 2125 to be roughly 2 in 3.

This may start with white collar work, but AGI is on track to impact every sector. Displaced workers may join blue-collar professions. On top of that, some blue collar work is on track to get displaced. Investment in self-driving vehicles for transportation and specialized robotics for manufacturing make those sectors ripe for displacement as well. The arrival of general-purpose robotics would replace the remaining blue-collar workers as well—and the robotics demos are becoming compelling.

This all means that, once AGI is on the scene, a whole lot of people will be making a lot less money, if they're earning at all. Once the robots finally show up, everyone might be out of a job.

But could we just expand the social safety net? Universal Basic Income for everyone?

Expanding the social safety net will be limited by several constraints. Fiscal constraints worldwide are tight due to rising rates and debts5. Economic modelling suggests that the truly explosive growth rates needed to fund widespread UBI will only arrive when we get general-purpose robotics. There are also many cultural considerations: many high-earning households may not be satisfied with earning the same UBI as everyone else, and losing the track to ambition they dreamed of, especially if they're early in their careers.

This is not hypothetical. We are starting to see pre-AGI systems shrink analyst classes and trigger layoffs. Remember that today is the worst these systems will ever be. As they get better, their impact on the labor market will grow rapidly. As Aschenbrenner says, "that doesn't require believing in sci-fi; it just requires believing in straight lines on a graph."

We will next look at the deeper problems and incentives that the loss of all work entails.

-

OpenAI claimed that GPT-4 aced the Uniform Bar Exam in 2023, performing in the 90th percentile of human test-takers, but a fairer comparison that fixes methodological issues reduces this to 48th to 69th percentile depending on your assumptions. ↩

-

For more on the rate of AI capabilities progress, see Aschenbrenner (2024), Ngo (2023), and Grace (2023), and Janků et. al. (2025). ↩

-

A natural decision when the decision-makers are the C-suite. ↩

-

We are at our most speculative here. But eventually it seems plausible that some firms would perform better if they were run by AI systems more capable than humans. Oftentimes, if it would be better, the market finds a way. However, we think there is hope that long-horizon planning, taste, and local knowledge might give humans an advantage over AIs in being CEOs for years. ↩

-

Social security, funded by payroll taxes, is expected to be exhausted in 2033. This would create significant pressure to shrink social safety nets at a time where (if innovation and diffusion and fast enough) voters may be demanding massive expansions. ↩